TCG Data Science: Analyzing Flesh and Blood

Background

About four months ago I decided to get back into Yu-Gi-Oh, a popular trading card game and obsession of middle school Harrison. My return to the game wasn’t physical but rather digitally via the recently released Yu-Gi-Oh Master Duel. You see, Master Duel provided a nostalgic window into my younger years without necessary financial investment. I can’t help but see it as a marketed form of escapist chronoportation aimed at my generation, but that topic is outside the scope of this post. For the sake of brevity I’ll just say that my experience with the game was not very positive, or rather my experience was not at all like the game I remembered as a kid. Modern Yu-Gi-Oh is very much a different game dominated by extensive combos resulting in a board state that aims to prevent your opponent from being able to play the game. Thus the typical player experience is as follows:

- If you’re going first: spend the next 10 mins running through your combo guide to set up your desired board state (or until the opponent resigns).

- If you’re going second: either wait the 10 mins to see if your opponent made any mistakes in their combo, or resign so that you can have a chance at another coin flip to go first.

I could probably spend an entire article dissecting the issues of the modern Yu-Gi-Oh metagame, but instead I would like to just focus on how dispirited I felt about the game after playing it at Platinum rank for a couple of months. I wasn’t dissuaded from trading card games in general though (after all, I remembered early Yu-Gi-Oh quite fondly), and thus I began to search for trading card games with the following core principles of a “fun” card game in mind:

- It should make you feel like you always have something to do or think about without getting bored. Turns should be quick with a lot of back-and-forth motion between the players.

- Combos are fun, but they shouldn’t be so complex that the average person couldn’t commit them to memory after reading them for a few minutes.

- Strategy should largely unfold over the course of a game, not over the course of a single turn.

- The game should avoid “omni-cards” that see utility in every deck. Deck composition should be as fluid as possible.

- Card rarity should largely be a collector’s concern. Common cards should see as much utility as rare cards.

- The game should avoid “dead cards” (aka Garnets). Every card in your hand should have multiple purposes.

- The game should be impossible to win on the first two turns. Going second should not feel like a disadvantage.

- (Bonus) The game should have a large enough player base and general support to make the investment of time and money worth it.

After peering into the metas of multiple TCGs, only one game stood out that appeared to uphold all of my established principles: Flesh and Blood.

Flesh and Blood

Flesh and Blood (FaB) is a relatively new trading card game with a decisive mission statement:

Our mission is to bring people together in the flesh and blood through the common language of playing great games.

Flesh and Blood rewards good decisions, not good luck. With our game, we seek to challenge the fundamental laws of TCG card evaluation and deck building philosophies. It’s highly interactive, with action beginning from the very first turn. The game is built around a unique resource system, underpinning an innovative combat dynamic which has been rigorously tested by competitive TCG fanatics.

In addition to meeting all of the core principles above, FaB distinguishes itself with some very interesting mechanical decisions. A game of FaB emulates the battle between two “heroes” in a fantasy setting - essentially characters you might create in a RPG. Each hero has a collection of equipment (their armor and weapon) and a deck of “attacks” or “spells” which is drawn from and played during each players turn. Each player starts the game with all of their equipment already “equipped” to their hero, which is then destroyed as needed during the act of playing the game. Because of this, you actually start the game at your strongest and weaken over time. This one choice of mechanics eliminates the typical rush to establish a desired board state in games like Yu-Gi-Oh. Another interesting departure is the concept of drawing cards at the end of your turn, forcing you to defend yourself on your opponent’s turn before you get to go on the offensive. You also draw into a new hand (typically four cards) every turn rather than drawing a single card, which reduces the impact of in-hand card advantage. Furthermore each card (with some exceptions, of course) may be:

- Played to activate its effect or deal damage to the opponent.

- “Pitched” to pay for the cost of another card.

- Used to defend against an opponent’s attack.

When a card is played or defended with, it is typically discarded to the graveyard where it (usually) remains for the rest of the game. Pitching a card to pay for the cost of another card, however, cycles it into the bottom of the deck so that it may be drawn again in the future. This mechanic instills the sense that the card is not “wasted” by using it to pay for something else.

Needless to say, I was immediately hooked. Flesh and Blood is easily the most fun I’ve ever had playing a card game. Each game feels fast-paced and balanced, with most matches in my experience ending in something like 2 to 0 (health out of typically 20), regardless of the heroes involved. Of course this game does have some issues in more competitive settings, particularly around certain equipment, but these issues are nowhere near the magnitude encountered when I was playing Yu-Gi-Oh (okay I promise I’ll stop complaining about that game from here on out).

So why am I writing a blog post about it? Clearly I must have found some way to incorporate computers or mathematics into my newfound passion, right?

You’re damn right I did!

Introducing fab

Recently over the past month or so, I poured … hold on …

~/projects/fab > cat $(find . -type f -name '*.py') | wc -l

6448

… 6448 lines of Python into a module (and accompanying Jupyter notebook environment) called fab for the express purpose of analyzing FaB card data. The goal is to develop a computational mechanism by which one may monitor the integrity of FaB’s metagame as it evolves over time. By developing computational methods to identify and expose flaws in the game, I believe we can better ensure the long-term integrity of FaB’s mission statement.

I am reminded of a talking point from this SAINTCON keynote by the LockPickingLawyer in which LPL describes that much of (lack of) security in the world of locksmiths is defined by the obscurity and secrecy in which the trade normally operates. In short most locks are laughably bad, lock companies know this, and the industry relies on that few know of that fact. The truth is however, that bad actors with malicious intent will inevitably learn how to bypass the physical security of the locks regardless of the general public’s knowledge on the subject. I argue that the same can be said about the mechanics of trading card games. I presume there either exists or will exist closed-source programs which may be purchased to simulate millions of games in popular TCGs like Magic: The Gathering with the goal to produce the deck statistically most likely to win at tournaments. I also presume (tin-foil hat time) that there either exists or will exist deep learning implementations of these simulators which could produce patterns and strategies less likely to be caught with more traditional methods. Those with the money to purchase (or technical knowledge to create) these simulators are (in my opinion) effectively at an unfair advantage over those that can’t. So what do we do about it? Well I would argue we do for Flesh and Blood what LPL did for the locksmith industry: develop a free, open source method by which we may computationally test the current metagame for vulnerabilities and “patch” them before they become too widespread. Ideally, Legend Story Studios (the creators of FaB) could run concept cards through the simulator to weed out any obvious game-breaking cards before internal playtests even begin.

At the time of writing this post, fab isn’t quite at the point of being able

to simulate games (even in a basic sense), but it does provides the groundwork

for analyzing the game in a traditional sense.

Basic Data Structures: Card & CardList Objects

Card data in fab is backed by the excellent work done by the

flesh-cube/flesh-and-blood-cards

repository. This data is imported and converted into

Card, and their associated collection

CardList. A basic typical workflow

of importing and working with these objects might look something like this:

from fab import Card, CardList

# Import all cards from disk into a `CardList` object. By specifying

# `set_catalog=True`, we are also telling the module that this object contains

# information for all cards, and thus may be referenced implicitly via some

# supporting methods.

all_cards = CardList.load('~/data/cards.json', set_catalog=True)

# One such supporting method is the ability to instantiate a card by its name.

prism = Card.from_full_name('Prism')

# `Card` objects are dataclasses.

print(f'{prism.health}, {prism.intelligence}') # 20, 4

# `CardList` objects have methods for sorting and filtering cards. The following

# would contain all Generic, Light, and Light Illusionist cards sorted by attack

# power.

supporting_cards = all_cards.filter(

types=['Light', 'Illusionist', 'Generic']

).filter(types='Warrior', negate=True).sort(key='power', reverse=True)

# `CardList` objects subclass `collections.UserList`, so all of the usual

# pythonic list workflows work.

for card in supporting_cards[:10]:

if card.is_attack():

print(f'{card.name}: {card.power}') # Prints name & power of first 10 cards

You pretty much get the idea. Card is a particular FaB card and CardList is

a list of cards. However both Card and CardList objects provide a number of

neat convenience methods that make working with them pretty slick. For instance,

you can grab the image for a card with .image():

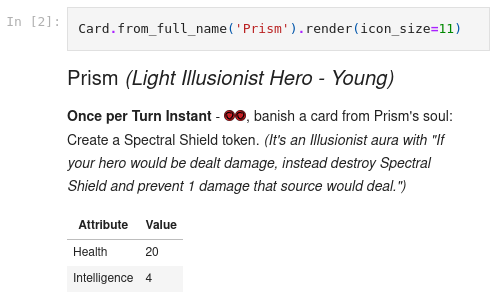

Or just render the card directly in Markdown:

Thinking about checking how much a card is worth on TCGPlayer? Easy:

print(prism.tcgplayer_url())

Wanna work with a card but only if it’s currently legal to play in Blitz?

if some_card.is_legal('B'):

# maybe put it in a deck here ...

else:

raise Exception(f'"{some_card.name}" is currently not legal in Blitz')

Next, we’ll go into the deck building capabilities of the module.

Building Decks

fab provides a special object to represent, and aid in the building of, player

decks called Deck (original, I know).

Deck objects contain not only the collection of cards within their “main” and

“side” decks, but also meta-information about the format the deck targets and

any arbitrary notes for using them. We can replicate our intended construction

of a Prism deck above using a Deck object like so:

from fab import Deck

# First, we build our `Deck` object.

deck = Deck(name='Prism Classic Constructed Deck', hero=prism, format='CC')

# From there, it's super simple to grab the list of all currently legal cards

# that can be included in our deck.

supporting_cards = deck.filter_related(all_cards)

# We can manually build out our deck via appending cards to the appropriate deck

# field.

deck.cards.extend(

supporting_cards.filter(name='Herald of Protection')

)

deck.inventory.extend(

supporting_cards.filter(types=['Arms', 'Chest', 'Head', 'Legs'])

)

But what if you don’t have time to build a deck? Well fab provides a couple

of options for you. Firstly, we can instruct fab to build one for us via the

auto_build() method. This process is essentially random, but with some

tweakable target goals (see the relevant

documentation

for more info):

deck.auto_build(

cards = supporting_cards,

target_pitch_cost_difference = 50,

target_power_defense_difference = 100

)

Finally, you can always pull a deck from FaB DB. This can be done like so:

# Essentially returns a list of dictionaries containing FaB DB links and other

# useful info.

results = Deck.search_fabdb(prism, format='CC', kind='competitive', order='popular-all')

# Once you have a deck chosen, importing it into the library is as easy as the

# following!

deck = Deck.from_fabdb('https://fabdb.net/decks/kEXYdXDp')

# You can even render any Markdown notes attached to the deck!

deck.render_notes()

Okay this article is getting long - let’s move on to the data analytics!

Analyzing Cards

Basic Statistics

fab provides easy access to basic statistical functions for CardList and

Deck objects. It can compute the maximum, minimum, mean, median,

mode, and standard deviation for all numerical card values (cost,

defense, health, intelligence, pitch, and power), as well as some

additional data of potential use such as the number of red, yellow, and/or

blue cards in a collection. Each of these computations may be performed

individually (ex mean_cost()) or collected all at once via the statistics()

method. Combined with the filtering and grouping methods, it’s quite easy to

build up meaningful statistical queries:

from fab import meta

# What is the mean power of all Runeblade attack cards that cost 0 resources?

answer = all_cards.filter(types='Runeblade').filter(types='Attack', cost=0).mean_power()

# How varied are the cost values of each hero class?

answer = {t, c.stdev_cost() for t, c in all_cards.filter(types=meta.CLASS_TYPES).group(by='types').items()}

Deck objects extend the workflows above by helping to pre-target cards for

computation. They also provide an overall statistics() method for quick deck

stats at a glance.

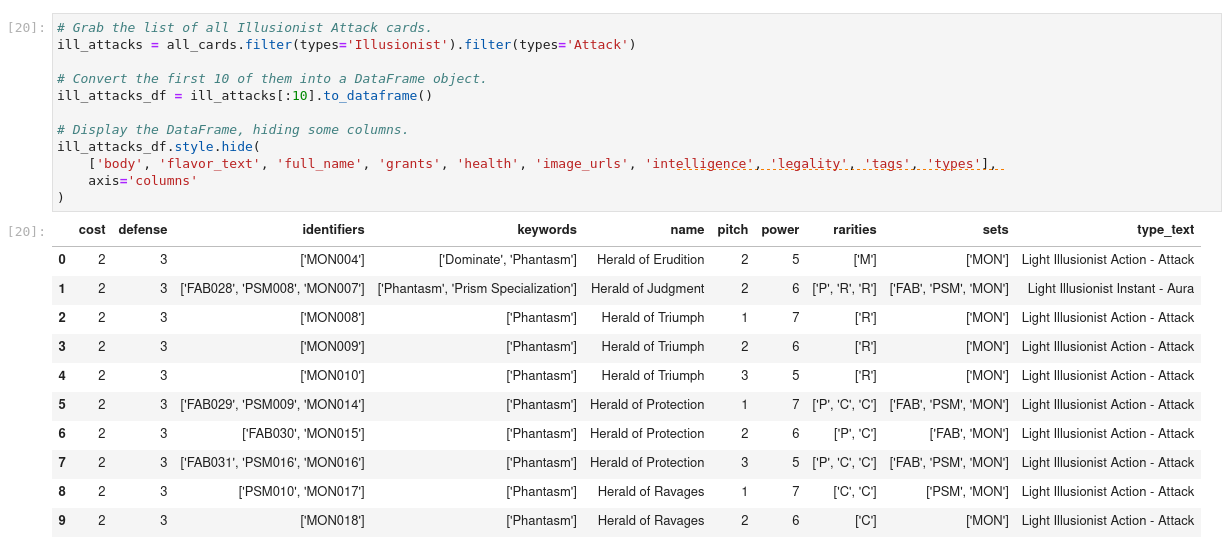

Converting To Other Formats

Though it may be hard to believe, most other python modules don’t have

first-hand support for working with Card or CardList objects. It became

apparent that the module should have the ability to convert to and from popular

data formats. For the moment, fab has the ability to convert Card objects

into pandas Series

objects, and CardList objects into pandas

DataFrame objects:

I figure direct interoperability with pandas will suffice for the majority of

use cases for the moment, although I foresee supporting direct conversions to

other formats in the future as well.

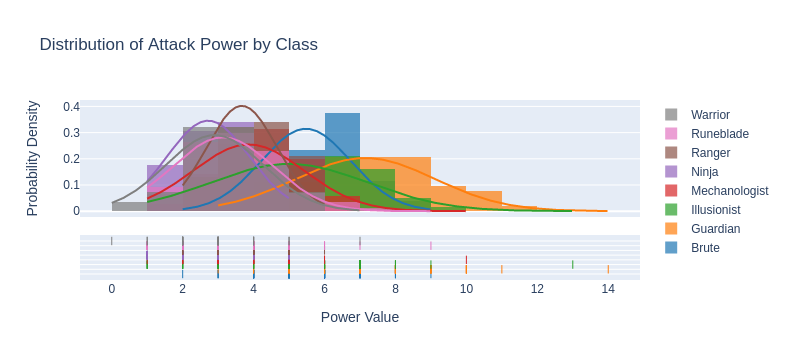

Graphical Analysis

Finally, fab provides some graphical analysis

shortcuts via wrapper functions around

Plotly, which allows one to make some cool looking

graphs:

Wrapping Up

So the TL;DR is that I absolutely love both the current state and potential of Flesh and Blood and wanted to leverage some of my skills to provide something back to the community that I hope can help this game maintain its course into becoming a true powerhouse like Magic: The Gathering or Yu-Gi-Oh. Honestly as I type this, I think it’s pretty much already there. Everyone I have showed the game to has had nothing but praise to give. My local community went from essentially zero players to just shy of a dozen in a matter of a few weeks. I’m happy to be part of a passionate, welcoming community for a fun game.